Table of Contents

Scientists Turn Tumor Immune Cells Into Cancer Killers

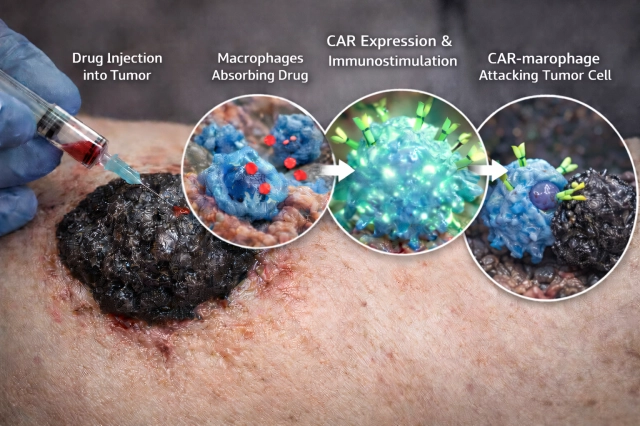

Researchers at KAIST have achieved a significant breakthrough in cancer immunotherapy by discovering how to reprogram a tumor's own immune cells into powerful cancer fightersdirectly inside the body. The discovery addresses a fundamental problem in oncology: tumors are densely packed with macrophages, specialized immune cells designed to attack cancer, yet these cells remain mysteriously silenced and ineffective against the very tumors surrounding them.

The Macrophage Paradox

Macrophages are white blood cells that normally function as the immune system's cleanup crew, engulfing pathogens and damaged cells. However, within the tumor microenvironment, these cells become co-opted by cancer cells through a process called polarization. Tumors secrete specific molecular signals that reprogram macrophages from their cancer-fighting M1 state into an immunosuppressive M2 state, which actually promotes tumor growth and metastasis. This transformation represents one of cancer's most effective evasion strategies.

The KAIST team's innovation lies in reversing this polarization process. By identifying the specific mechanisms that silence macrophages within tumors, the researchers developed a method to reactivate these cells' tumor-killing capabilities without requiring external cell engineering or transplantation. This in-situ approach is fundamentally different from existing CAR-T cell therapies, which involve extracting immune cells, modifying them in laboratories, and reintroducing them into patientsa process that is expensive, time-consuming, and not universally effective.

Mechanism and Clinical Implications

The breakthrough targets the molecular pathways that tumors use to suppress macrophage function. By disrupting these suppressive signals, the research team demonstrated that dormant macrophages could be awakened to recognize and eliminate cancer cells. This approach offers several advantages over current immunotherapy methods: it leverages cells already present in the tumor, eliminating manufacturing delays; it reduces costs associated with ex vivo cell engineering; and it potentially minimizes the risk of systemic immune complications that can arise from introducing large numbers of modified cells into circulation.

The implications extend across multiple cancer types. Since macrophage infiltration occurs in virtually all solid tumorsincluding pancreatic, breast, lung, and colorectal cancersthis discovery could provide a broadly applicable therapeutic strategy. The research suggests that many cancers may be vulnerable to this reprogramming approach, offering hope for patients with currently difficult-to-treat malignancies.

Broader Context in Cancer Immunotherapy

This discovery arrives amid a period of rapid innovation in cancer immunotherapy. Recent research has also revealed how pancreatic cancer evades immune detection through molecular tricks involving the MYC protein, which simultaneously drives cancer growth while suppressing immune alarm signals. Understanding these evasion mechanismsand now, how to counteract themrepresents a paradigm shift in oncology.

The KAIST findings complement other emerging approaches, such as checkpoint inhibitor therapies that release immune brakes, and engineered T-cell therapies. However, the ability to reprogram existing tumor-resident immune cells offers a unique advantage: it works with the body's existing defenses rather than requiring external intervention.

Path to Clinical Application

While the research represents a significant conceptual advance, translating this discovery into clinical treatments will require additional development. The team must identify the specific molecular targets for therapeutic intervention, develop drugs or biologics that can safely and effectively reprogram macrophages in human patients, and conduct clinical trials to establish safety and efficacy profiles.

The timeline for clinical availability remains uncertain, but the fundamental breakthroughdemonstrating that tumor-resident macrophages can be reprogrammed into cancer fightersopens a new therapeutic avenue. If successful in human trials, this approach could complement existing immunotherapies or serve as a standalone treatment for patients who have not responded to conventional options.

This discovery underscores a critical principle in modern cancer research: tumors are not monolithic enemies but complex ecosystems where cancer cells manipulate their environment. By understanding and reversing these manipulations, scientists are developing increasingly sophisticated weapons against cancer.