Table of Contents

Breakthrough in Memory Science: Chaperone Protein Powers Persistent Memories

On January 26, 2026, researchers at the Stowers Institute for Medical Research announced a pivotal discovery: a tiny chaperone protein that guides the brain's formation of functional amyloids, transforming short-term experiences into long-lasting memories. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on January 30, 2026, this study builds on decades of work by the Si Lab, expanding from simple sea slugs to complex human brains.

From Sea Slugs to Human Brains: The Amyloid Revolution

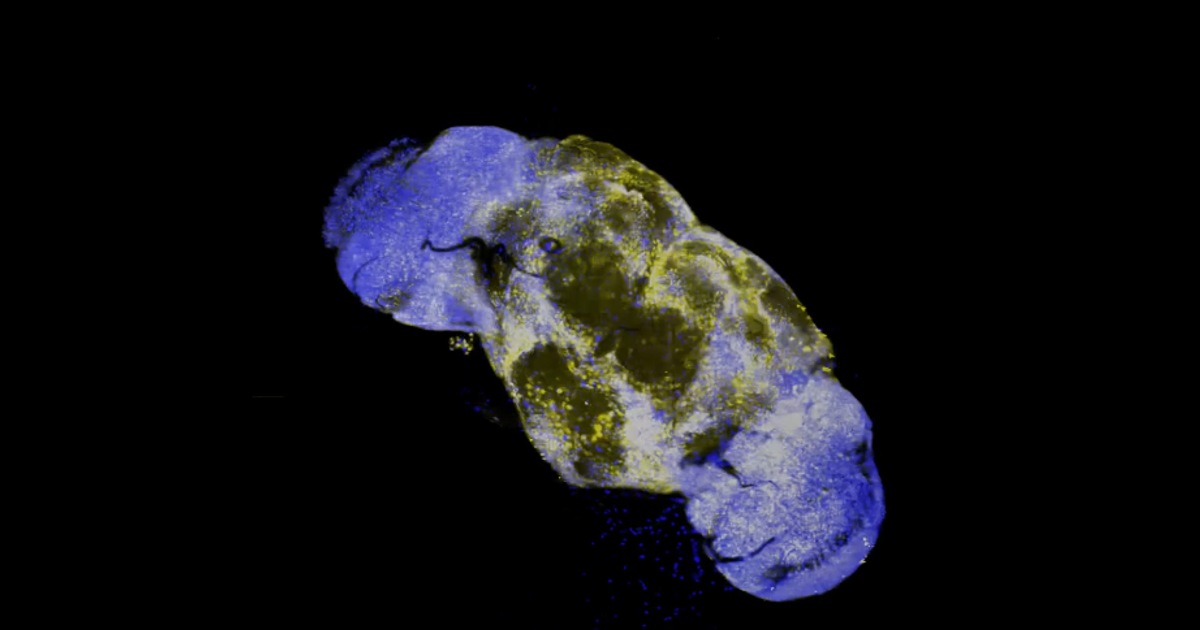

The journey began in 2003 when Kausik Si, a neuroscientist at Stowers, identified functional amyloids in the sea slug Aplysia, which has just 10,000 neurons. Unlike toxic amyloids linked to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, these structures stabilize synaptic changes, enabling memory persistence. Si's team scaled up: fruit flies (150,000 neurons), mice (70-80 million neurons), and humans (86 billion neurons) all employ amyloid-based mechanisms for durable memories.

Amyloids are protein aggregates with beta-sheet structures, typically infamous for misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. However, functional amyloids serve beneficial roles, like prion-like propagation of synaptic strength. The new study identifies the chaperone proteinunnamed in the release but central to the mechanismthat shepherds fragile protein oligomers into stable, prion-like amyloid forms at synapses.

The Chaperone's Role: Precision Engineering of Memory

Chaperone proteins assist proper protein folding, preventing aggregation. Here, the discovered chaperone specifically promotes amyloid formation for memory. During learning, neuronal activity triggers cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein (CPEB), which oligomerizes and converts to amyloid. The chaperone ensures this transition yields functional, non-toxic structures, overriding disease-causing amyloids.

"Discovering this chaperone protein has now provided us with an avenue to potentially approach amyloid-based diseases in an unanticipated way," Si stated. Activating it could redirect toxic amyloids to benign forms or boost memory capacity.

Technical details reveal the chaperone's action: it stabilizes oligomers during the lag phase of amyloid formation, accelerating fibril growth while maintaining functionality. In mouse models, disrupting this process erased long-term memories, confirming its necessity.

Implications for Disease and Enhancement

This flips amyloid research: instead of solely clearing aggregates, therapies could harness chaperones. For Alzheimer's, where amyloid-beta plaques dominate, activating the chaperone might prioritize functional amyloids, mitigating pathology. Si envisions treatments endowing brains with enhanced amyloid capacity to counter disease intrusion.

Beyond pathology, cognitive enhancement beckons. Boosting chaperone activity could amplify learning in healthy brains, with applications in education or aging-related decline. The study's cross-species validationfrom invertebrates to mammalsunderscores evolutionary conservation, bolstering translational potential.

Broader Context and Future Directions

The Si Lab's work challenges amyloid dogma, established since the 1980s linking them solely to disease. Recent years saw functional amyloids in bacteria (curli), fungi (prions), and plants, but neural roles were speculative until Si's sea slug breakthrough. Expansion to vertebrates solidified the paradigm.

Future research targets: identifying the chaperone's structure for drug design, testing in disease models, and human trials. Si calls it an "unknown universe," exciting for novel therapies rooted in humble origins.

Media buzz includes Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News coverage on January 26, 2026, highlighting the mechanism's role in unforgettable moments.

This discovery positions 2026 as a landmark for neurobiology, bridging basic science and clinical hope. Contact: Joe Chiodo, [email protected].